For my response paper, I chose to analyze one of my favorite stories in literature and film; Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita, first published in 1955. Seven years later, in 1962, Nabokov and Stanley Kubrick adapted the novel into a feature film, which received an Academy Award nomination for screenwriting in 1963. In my response, I will be comparing the literature and film adaptation, as well as finding contrasts and correlations with related text from Foucault and McDonald. Not only is this one of my most cherished college novels and most respected of Kubrick’s films, I also feel it’s the most controversial of any subject matter I have ever experienced. In fact, Nabokov finished the novel in 1949, but was rejected from numerous American publishers because of its taboo themes. It took six years until a French publishing company, Olympia Press, finally took notice of Nabokov’s masterpiece and put the novel into circulation, and years later for American readers.

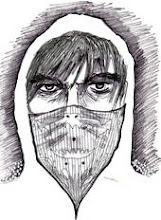

The protagonist of Lolita, Humbert Humbert, or H.H., is an educated, middle-aged college professor who has just moved to New England in search for a residence to live and work. He shortly finds a room under Charlotte Haze, and decides to move in due to his infatuation with her twelve-year-old daughter, Dolores, also nicknamed Lolita. In Nabokov’s story, we are introduced to the protagonist, knowing that he has a fixation with “nymphets” as he describes, or young, underage girls to be blunt, and confesses his forbidden desire to destroy the conventions of love and sexuality. H.H. spends the rest of the novel acknowledging his crimes and tries to justify it as a force of nature and not a psychological imbalance or genetic induced pleasures. In fact, H.H. and even Nabokov are critical of psychiatry, Freud, and of the human dilemma and boundaries of sexuality. Nabokov allows us to deconstruct H.H. as a human being with many flaws, being a pedophile and a murderer, and we are obligated to sift through H.H.’s clever usage of words and imagery to understand, or even accept the human condition. In contrast, Foucault attempts to state the history of “aberrant sexualities” through games of “perpetual spirals of power and pleasure” as a way of explaining the sexual inconsistency and reality of the individuals and those who classify them. Nabokov destroys these conventions and explanations through H.H.’s narration, not allowing the point of view of the observers, outside society, or reality into his confidential love. The narration of the story from H.H. states that his attraction, perversion or “pleasure” doesn’t derive from the evasion of an apposing law, construct or “power”, but is much more innate. H.H. describes his love through a journal, using vivid, magical phrases to compare his emotion to a trance, spell or euphoria. Like Foucault states, from a readers’ point of view, we are classifying, rather than condemning H.H. as a human being and not as a mental patient. The emotion is uncontrollable and natural for Humbert, and so he marries Charlotte to abide by societies normalcy, only to be secretly to be closer to his love. Charlotte then dies after finding H.H.’s journal, thus allowing H.H. to pursue his Lolita without interference, but now, unfortunately, as a father figure and not a lover. Lolita and H.H. go into exile from normal society, in secrecy from suspicious observers, but eventually Lolita grows up. H.H. tries to control Lolita, tries to run away with her, or even marry her, but Lolita, now aware of the situation, goes into her own exile, and marries a man half way across the country. H.H. dies in a jail cell, awaiting a trial for the murder he committed against the man that took Lolita from him. H.H. dies alone, heartbroken and widowed, only with his journal to pass on to future psychiatrists.

In comparison from the book to Kubrick’s version (and even the 1997 remake) of the film, one could refer to McDonald’s chapter on the “Sex Comedy”: a time when the subject of even legal, heterosexual sex was considered taboo. The film, made in 62, within the limits of censorships and the Production Code Administration was considered controversial because it acknowledged the forbidden “sexual perversion”, which was one of three taboos, McDonald states, that held the weakened PCA code together until 1966. Indeed, Kubrick could not portray the love between H.H. and Lolita as effective as Nabokov could, so Kubrick uses imagery and subtext within words to point out the blatantly obvious. Kubrick opens the film with foreshadow of H.H. killing a man who is also fond of Lolita, which is actually the last chapter in the book. We then cut to the introduction of H.H. as a narrator and his discovery of Lolita. Kubrick does this to get the categorization of H.H. as a murderer out of the way so we may concentrate on the more important aspects of H.H.’s subconscious and condition. Like Nabokov, Kubrick forces us to relate with H.H., his narration, usage of illustrative words, making us pedophiles, and at the same time, accepting it as just another part of the human condition. The film never received as much recognition as the 1958 American release of the book, which was controversial, yet a bestseller, because the film couldn’t achieve the graphic intensity, flow of emotions and clever usage of postmodern literature as Nabokov did. Overall, the subject matter of pedophilia may never be accepted in modern society, but we cannot dismiss that it exists. The book is still banned from every high school and more than 1/3 of countries in the world, but I think that is also why it is so highly accepted and intriguing as a form of classic literature that dares to question the conventions of passion, love and sexuality.

Works Cited

Foucault, Michel “The Perverse Implantation.” The History of Sexuality Vol. 1: The Will to Knowledge. London: Putnam, 1976.

McDonald, Tamar Jeffers. Romantic Comedy, Boy Meets Girl Meets Genre. London: Wallflower Press, 2007

Nabokov, Vladimir. Lolita. France: Olympia Press, 1955. New York: Putnam, 1958.

Lolita. DVD. Dir. Stanley Kubrick, Warner Brothers, 1962

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

1 comment:

Ye gods I haven't seen Kubrick's Lolita version in years--must now rewatch after mid-terms, no thanks to you. That aside, love your analysis of the film and novel. Considering Kubrick as a film auteur, what do you think is the fundamental theme in all his films? and if I had any thing to further add to your analysis and use of Foucault's analysis in comparison, try your hand at Kubrick's "Eyes Wide Shut", the European version of course, or David Lynch's "Muhulland Dr." That should be great fun, don't you think?

Post a Comment